“Mindfulness at its best, at its most healing and most powerful, is a way of life, a way of being in the world, with more presence and compassion”

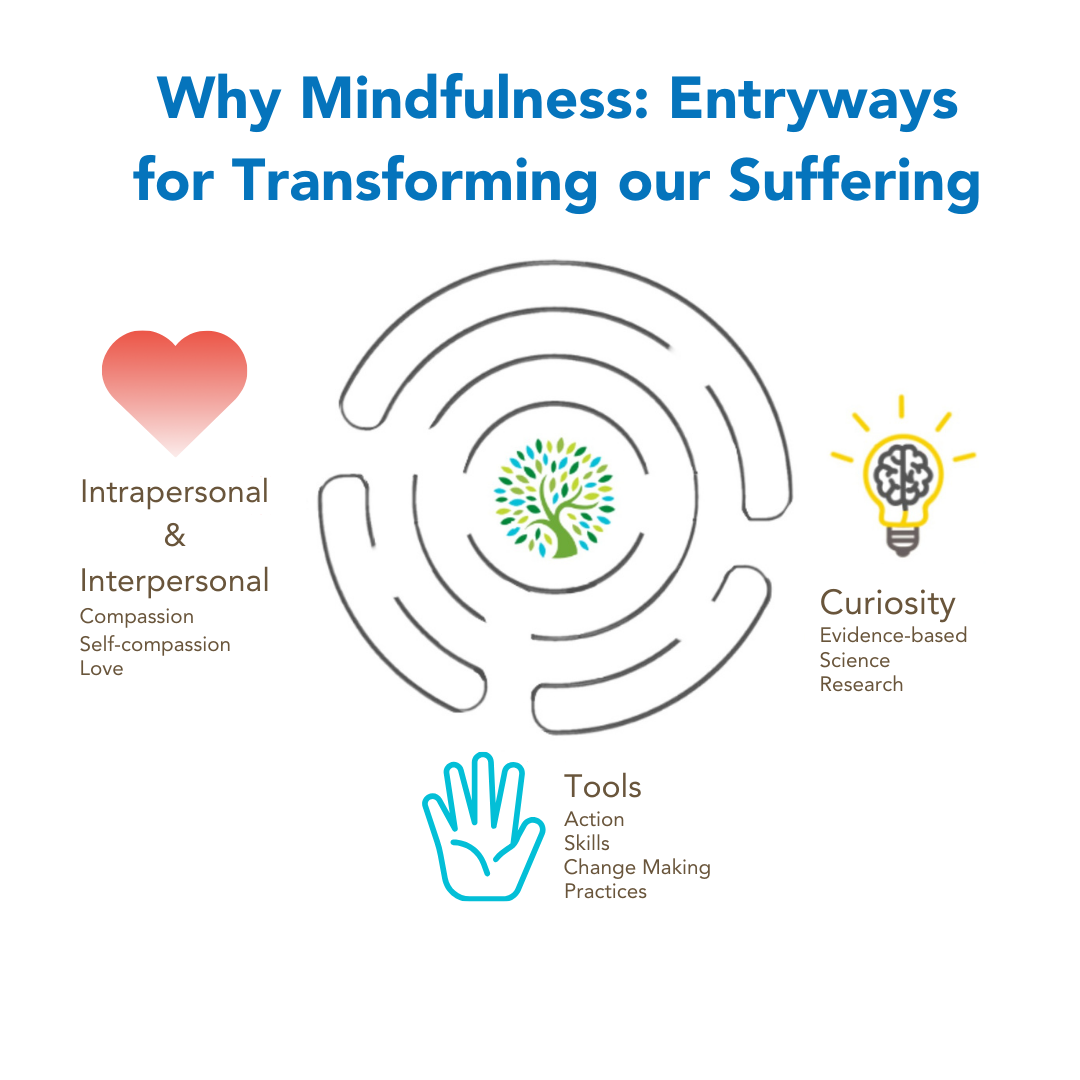

Why Mindfulness? Entryways to Mindfulness

At BC Children’s Hospital Centre for Mindfulness, we aspire to foster a more mindful hospital where mindfulness and compassion guide every aspect of our hospital culture and care. But why would a patient, parent/caregiver, or health professional at our hospital want to learn and practice mindfulness in the first place? Just as every person has their own journey in life and growth, every minfulness practitioner has something that initially drew them into mindfulness. Quite often, this initial motivation had something to do with a deep suffering that a person is experiencing. Suffering is distinct from a symptom or an illness. As Dr. Eric Cassell wrote in 1999, suffering seems related to the meaning of a symptom, fear of the future, or a threat of integrity to the person. Mindfulness in health care has been deeply influenced by the Buddhist tradition, in which mindfulness is embedded in a larger “eightfold path” that is primarily concerned with the alleviation of suffering. At a more mindful hospital, alongside the conventional and important work of diagnosing and treating symptoms and illness, we also hope to to recognize suffering that often accompanies illness and health care, and offer a path to the transformation of suffering.

In our hospital community, we have observed three common “entryways” into mindfulness, three initial motivations that might draw people in to the practice. We can call these entryways “heart – hands – head.” Each entryway may appeal to different people, who have varying interests, affinities, and ways of thinking. Each path is valuable, and each person is a precious member of our mindful hospital community.

“Heart” – Intrapersonal + Interpersonal Mindfulness

The entryway of the “heart” speaks to people who are strongly motivated by values such as love, compassion, and caring. For some people, these may be cultural or spiritual values, that we have learned from our teachers and ancestors. Parents and caregivers love their children unconditionally, and their caretaking of children is itself an act of love. For health professionals, many of us were drawn into the healing arts initially motivated by values of love, but it can be hard to use that word in the health professions as it may feel “unscientific” or “unprofessional” in the context of our medical culture. We believe that compassion and love can be a powerful force in health care, and we want to challenge ourselves to be courageous and bring these values to the forefront. As Zen Teacher Brother Phap Dung once described, the Vietnamese word for Hospital is nhà thương, which literally translates as “house of injury.” The Vietnamese language is full of poetic double meanings. Thương also means love, and nhà thương can also have a double meaning, as house of love. Imagine if hospitals were truly a place of love for all of us, patients, caregivers, and staff who come through the doors with suffering!

Intrapersonal mindfulness is the practice of bringing this presence and compassion to ourselves. This can be described as self-compassion, or inner compassion. Kristen Neff and Chris Germer have pioneered a program called Mindful Self-Compassion, which builds coping and resilience, improves our mental and physical wellbeing, and can help us to learn, grow and succeed in our goals. Interpersonal mindfulness is the practice of bringing our own individual mindfulness practice into our relationships, our communication, our teaching, and our advocacy. Mindfulness is not for individuals alone, and interpersonal mindfulness recognizes that we as human beings are deeply interconnecteded, in both our suffering and our liberation. The field of interpersonal neurobiology demonstrates that mindfulness, like stress, is “contagious.” We believe that the conditions for healing and transformation can be cultivated in this interpersonal space. We can best reach our full potential for mindfulness and the transformation of suffering together, in what Dr. Martin Luther King called the “Beloved community.”

“Hands” – Practical Tools

The entryway of the “hands” speaks to a very practical motivation to find tools to address a challenge or difficulty we may be facing in our lives. Often this is a very specific difficult situation in life, such as needing to find a way to cope with stress, depression, anxiety, or trauma; or survive a serious health condition; or handle chronic physical or emotional pain. The field of Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBI’s) has exploded in the last 15 years. Now, there are standardized and evidence-based mindfulness interventions in a variety of settings from health care to education, and with a variety of populations from adults with cancer, to youth with chronic pain, to health care professionals experiencing burnout, to parents and caregivers. Mindfulness has been found to be practical and cost-effective in a variety of settings, not as a panacea or cure-all – and certainly not as a replacement for changing systemic factors and injustice that lead to illness and suffering – but as one part of a larger strategy of supporting wellness and coping in the face of stress, pain and illness. Often, people who sign up for a mindfulness “stress reduction” course, find that the initial stress reduction was just the “appetizer” on a lifelong mindful journey of discovery, growth, and transforming deeper suffering.

“Head” – Curiosity

The entryway of the “head” speaks to an intellectual and scientific curiosity in the emerging field of mindfulness. The American Mindfulness Research Association has tracked the explosion of studies and publications on mindfulness in the scientific literature. Neuroscientists are documenting how mindfulness can change the way the brain functions in response to pain and distress. Many mindfulness practitioners and scholars are fascinated by the intersections between ancient wisdom and modern science. As scientists advance the research and understanding of mindfulness, we can make the best use of it, and better manage some of its potential pitfalls and limitations as well. When the “heart,” “hands” and “head” come together, we are able to access our full humanity, and bring the wisdom that can arise from that to the most pressing problems of illness and suffering, living and dying.

Mindfulness is a Path

Regardless of the entryway that one initially uses to finds their way into mindfulness, many of us discover that mindfulness can be much more than what we originally thought. Mindfulness can be more than means to an end. Mindfulness can be much more than meditation, or a tool to manage a specific symptom. Mindfulness at its best, at its most healing and most powerful, is a way of life, a way of being in the world, with more presence and compassion. Here, we are representing this mindful path with the ancient image of the labyrinth, which represents mindfulness as an infinite journey, not a destination. No matter where we are in our own life journey and mindfulness path, with the mindful quality of “beginner’s mind” and curiosity, our mindfulness practice is always beginning, never ending. We can always discover new ways of strengthening our presence and love to ourselves, and to our mindful hospital community. Please join us on this path!