Note: This is the first installment of a three part series exploring how ancient wisdom teachings may be relevant for health care professionals. For more, see the second installment and third installment of this ongoing series.

Part 1, Introduction To This Series:

My intention with this series is to offer some of the most transformative and helpful teachings and practices that I’ve learned from Buddhist traditions, primarily from the Engaged Buddhist Tradition of Plum Village, taught by Vietnamese Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. I hope to offer the most precious fruits of these teachings in a way that is relevant and non-sectarian, grounded in love, compassion, and awareness that are universal human capacities. The “Three Jewels” (also called Three Gems, Three Refuges) and “Five Mindfulness Trainings” (also called Five Precepts) are core teachings in this tradition. I will attempt to “re-interpret” the trainings in a way that might speak to us as pediatric health providers. No one needs to be a Buddhist, or a member of any particular religion, to contemplate these trainings and practices. The essence of these teachings are found in wisdom traditions around the world.

Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen said, “Medicine is a spiritual path, which is characterized by compassion, harmlessness, service, reverence for life, courage and love. The basic qualities of the Hippocratic oath are not scientific qualities, they are the qualities of human relationship, and they are spiritual qualities, very profound spiritual qualities.”[2] For some of us, what drew us to into the healing arts was a spiritual calling. I invite you to inquire with an open heart and open mind to see if any of these insights resonate with you, and if any of the practices are things you are already doing in your life, or might wish to try.

The Three Jewels are a foundational teaching throughout Buddhist traditions in Asia[3]. They are often translated as “The Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.” In the Plum Village community, we invoke these jewels with the following chant:[4]

“I take refuge in the Buddha,

the one who shows me the way in this life.

I take refuge in the Dharma,

the way of understanding and of love.

I take refuge in the Sangha,

the community that lives in harmony and awareness.”

For this series, I am translating Buddha as “Mind of Wisdom and Heart of Love,” Dharma as “The Path of Presence and Love,” and Sangha as “Mindful Health Care Community.” These jewels are not something external or supernatural that we are expected to have blind faith in. Rather, they are ingredients and supports to our spiritual lives that we already have within us, and we are in them. I have translated “I take refuge” as “I have confidence in.” When we recite and contemplate the three jewels, we look deeply into how these elements are already alive in us. By inviting this intention, we can “water the seeds” of these elements that are inside of us, helping them to manifest and flourish in our daily work.

The Five Mindfulness Trainings (or Five Precepts) have a history going back 2,600 years, to the time of the historical Buddha. For me, the trainings are a way of bringing mindfulness into every area of life and my daily decisions. They are the ethical foundation of mindfulness practice. The trainings are not hard and fast rules, and they are not weapons with which to judge ourselves or others. Rather, they are invitations to examine areas of our life, and to guide our daily decisions in a way that avoids causing harm to ourselves and others. Thich Nhat Hanh has rendered each training beginning with the sentence, “Aware of the suffering caused by…”, which helps to bring awareness to the direct and indirect impacts of our daily decisions.

How to Practice These Contemplations: Each of the three jewels and five mindfulness trainings can be an object of contemplation to meditate on. I invite you to find a few minutes of stillness. You can be fully present in your body, and in your breathing, inviting a spirit of curiosity. When you are ready, you may wish to read one contemplation at a time, silently or out loud, alone or with others, observing what arises in your heart, body, and soul. Find a few more moments if silence. Consider reading the contemplation again. When you are finished, you may wish to journal about what you noticed, or share with a trusted friend or colleague.

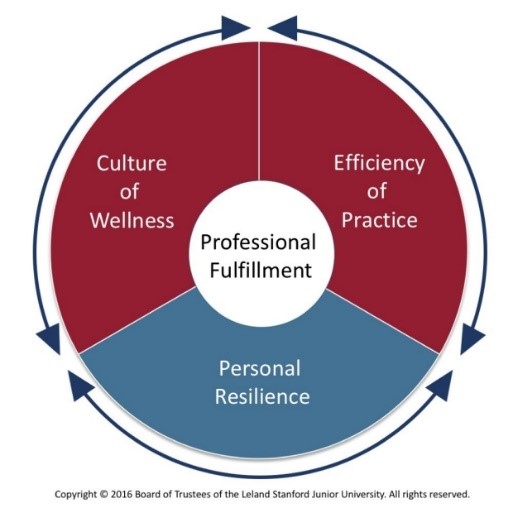

Limitations of Meditation: I want to acknowledge that mindfulness practices are only one part of professional fullfillment. Following the Stanford Model of Professional Fulfillment[5], the major factors driving health professional burnout are systemic factors, including culture of wellness and efficiency of practice. I am definitely not saying, “Just meditate, and ignore systems problems.”

At the same time, I would challenge what I consider to be a false dichotomy: That we can choose either personal resilience to cope with distress, OR systemic change to address some root causes of this distress. Instead, I would propose in the spirit of “spiritual activists” and changemakers such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., that mindfulness can provide wisdom and energy for effective and sustainable leadership, advocacy, and systems change. As Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh says, “Mindfulness must be engaged. Once there is seeing, there must be acting. Otherwise, what's the use of seeing?”[6]

Part 2: First of the Three Jewels, Mind of Wisdom and Heart of Love

Health Care Professionals version:

I have confidence in my capacity for wisdom and the love. I was born with this capacity, and this vision has called me to become a healer. Sometimes systemic problems and exhaustion obscure my original vision and motivation, but I know that it is still there, and I can call on it whenever I choose to. I can also call on the many people who have walked this path before me, teachers both known and unknown to me personally, who have taught the way of love and compassion in health care and in society. These are historical figures, and these are my own teachers and mentors. Those people have not only inspired me in the past, but they are also a part of me in the here and now. I can call on their wisdom to help me know what to do and how to do it in my work as a healer. I know that have the capacity to embody love and wisdom in my work in health care. I commit myself to remembering, nourishing, and strengthening this capacity in my daily life.

Commentary:

As a physician, I have often been uncomfortable using the word “love” in professional settings. I’ve worried that the word may sound too unscientific, or too personal. I am been inspired by people like Dr. Herbert Friedman, who studied adolescent development for the World Health Organization, and summarized the science on the topic in one sentence: “Love is the most important ingredient in human development.”[7] My mentor in Adolescent Medicine, Dr. Kenneth R. Ginsburg from the The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, writes, “Love is seeing someone as they deserve to be seen, as they really are, not according to a behavior that they might be displaying, a label they might have received, or what they might be producing.”[8] He also writes, “Why do we love? Because it makes our children know they are worthy of being loved.”[9]

As a mindfulness practitioner, I have found that love is the most powerful energy that I can access. I have also found that love is most important precisely in those moments when it is most difficult to feel loving. I hope to bring my full self to my work as a healer, in alignment with the values that give me motivation and meaning. I have learned from author and social critic bell hooks[10] that love is a decision, a commitment, not just an emotion that comes and goes on its own whims. The practice of mindfulness and Buddhism have given me a discipline to cultivate and develop my own capacity for love, both in my personal life and in my work as a health professional.

In traditional Buddhist contexts, the first of the Three Jewels is often translated as “Taking refuge in the Buddha.” In Zen practice, “The Buddha” is not a deity outside of us that we worship. The word Buddha literally means “awakened being,” and as Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh says, “We are all part time Buddhas.” We can consider “The Buddha” to be our own mind of awakening and heart of love. Sometimes we forget, or lose touch with, our capacity for wisdom and love. This is especially true in challenging times, for example, when we are stressed at work, when we are faced with suffering or blame, or when we are experiencing conflict, burnout, or moral distress. These are precisely the times when we need a practice, and we need to remember our strengths and our capacities for wisdom and love.

Contemplating the first jewel reminds us of our original aspiration, why we came into the healing arts in the first place. It also reminds us that we are not alone on this path, and that we can rely in the wisdom of generations of wise teachers who have come before us. We can call on the “Buddhas” within us, and this helps us to uncover our own “Buddha nature.” And, we don’t need to be a “Buddhist” do any of these things!

Part 3: Second of the Three Jewels, The Path of Presence and Love

Health Care Professionals Version:

I have confidence in the many ways of cultivating awareness and love that I have learned from wisdom traditions, and my own life experience. I know that I, and all people, were born with the seeds of awareness and love. I know that I can cultivate and strengthen these capacities every day, so that they show up more and more in my daily life as a healer. Practices such as mindfulness can help me to stay more present and more loving in my every interaction with patients, families and caregivers, and colleagues. With intention and training, I can learn to show up with presence and love even in the face of deep suffering. I know that I can grow and deepen my capacity for loving presence day by day, remembering that if I am there for my practice, it will be there for me. I can also remember to invite compassion for myself during those inevitable times when I miss the mark, remembering that all humans miss the mark sometimes. I can learn to see every moment as an opportunity to come back home to the present moment, and begin again. With gratitude, I take refuge in this path, a lifelong journey of discovery and growth.”

Commentary:

In my years of practicing mindfulness, I’ve noticed a fascinating paradox. On the one hand, mindfulness is instant, it is like the ultimate mobile app. I can bring mindful present-moment awarenes to any moment, anywhere I am, with just one breath. On the other hand, I need to cultivate it as a lifelong intentional habit, in order to remember and be able to use it when I need it. Otherwise, it’s just an idea, a nice sounding philosophy or theory that does not actually come alive in my daily life.

My personal definition of mindfulness, adapting from Dr. Jon Jabat-Zinn’s classic definition[11], is “Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way: On purpose, in the present moment, and with unconditional love.” Other translations and definitions of mindfulness can include “heartfulness,” or “present-heartedness.” These translations invite us to not only pay attention and concentrate and focus on the present moment, but to do so with a spirit of affection, of kindness, and of compassion. This is especially useful when dealing with pain and difficulties. In my own experience, just simply paying attention to pain, without embracing it with self-compassion or heartfulness, usually just makes me suffer more. On the other hand, when I stay present as best I can with my own pain and the pain of others, with unconditional compassion and open-heartedness — I find that I can touch the possibility of transformation and liberation. I add the word “unconditional” to remind myself to invite these qualities when it is pleasant and easy, as well as when I am in a difficult situation or experiencing suffering. I try to remind myself of my aspiration, as well as practice kindness for myself when I forget, or miss the mark.

The Pali word “sati” which is the root of the English word “mindfulness,” can also be translated as “memory,” or “remembering.” I love this translation, because our aspiration for our mindfulness practice can be to remember what is already there. Contemplating this training reminds us of the our innate wisdom and love. Every time we remember, every time we remind ourselves, it strengthens the neural networks in our brains that are associated with these capacities of wisdom and love. The more often we do that, the stronger these capacities become, which helps us to access them in times of need, especially when things are difficult.

An intentional life habit like mindfulness has a life of its own. Just like any living thing, if we do not feed it and care for it, it will whither away and die. On the other hand, if we make a conscious decision live more mindfully in our daily lives, it will nourish us. Mindfulness is not a personality characteristic that we either are born with or not. It is a daily practice, it is a choice that we can choose to make, moment to moment, day to day. The more we train our minds in the direction of awareness and love, the more it shows up in practical ways in our daily work in health care. If we are there for our mindfulness practice, our mindfulness practice will be there for us!

[1] Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982 Mar 18;306(11):639-45. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198203183061104. PMID: 7057823.

[2] Rachel Naomi Remen with Krista Tippett. On Being with Krista Tippett. https://onbeing.org/programs/rachel-naomi-remen-how-we-live-with-loss/

[3] https://tricycle.org/magazine/the-three-gems/

[4] https://plumvillage.org/library/chants/the-three-refuges/

[5] https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about/model-external.html

[6] Thich Nhat Hanh, Peace is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. Bantam, 1992.

[7] Friedman HL. J Adolescent Health. 1993;14:509

[8] Ginsburg KR, McLain ZBR, eds. (2020). Reaching Teens, 2nd Ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2020.

[9] Ginsburg KR. Congrats – You’re Having a Teen! Strengthen Your Family and Raise A Good Person. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2023.

[10] hooks b., All About Love: New Visions. New York: William morrow, 2000.

[11]“Paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally.” Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York, NY: Hyperion; 1994